Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD): The “Hidden” Variable Controlling Your Yield

In controlled environment agriculture, growers often obsess over temperature and humidity independently. They set the AC to 75°F and the dehumidifier to 55%. But plants don’t respond to these settings in isolation—they respond to the relationship between them.

That relationship is captured by a single, powerful metric: Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD).

VPD is the “hidden” lever for controlling plant growth, nutrient uptake, and stress. When properly managed, it acts like a high-performance fuel pump, driving water and nutrients from the roots to the shoots. When ignored, it quietly limits performance—even in rooms that “look” perfect on paper.

What Is Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD)?

Technically, VPD measures the difference (deficit) between how much moisture the air can hold versus how much it actually holds at a specific temperature.

The “Straw” Analogy: How Plants Drink Think of VPD as the suction force on a straw.

-

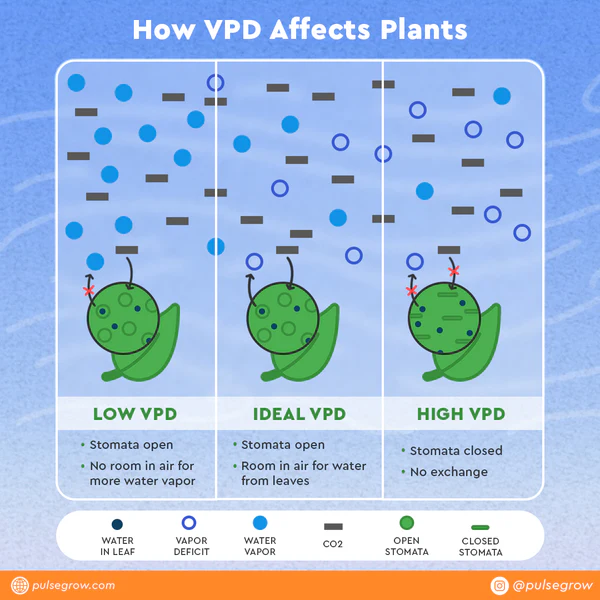

Low VPD (Low Suction): The air is wet and thick. The “suction” is weak. The plant struggles to transpire, meaning water (and the nutrients dissolved in it) sits stagnant in the roots.

-

High VPD (High Suction): The air is dry and thirsty. The “suction” is too strong. The plant loses water faster than it can drink, causing stomata to close in defense, which halts photosynthesis.

-

Optimal VPD (Perfect Suction): The “Goldilocks Zone.” The air pulls water through the plant at the exact rate the roots can replenish it. This maximizes nutrient flow and gas exchange.

Why VPD Matters More Than Temperature Alone

Relative humidity (RH) is just a percentage. It isn’t a biological signal. A room at 65% RH can be paradise at 75°F but a recipe for mold at 60°F.

VPD translates these two variables into a single number that reflects plant stress. It directly influences:

Stomatal Regulation: Are the plant’s “pores” open to eat CO₂?

Transpiration Rate: Is water moving through the xylem?

Nutrient Uptake: Calcium and magnesium move only with water. If transpiration stops (Low VPD), nutrient uptake stops.

Air VPD vs. Leaf VPD: What Plants Actually Feel

Most grow rooms measure the air on the wall. But plants live at the leaf surface.

Because plants sweat (transpire) to cool themselves, healthy leaves are often 2–5°F cooler than the surrounding air. This means the VPD at the leaf is different from the VPD on your sensor.

High-performance cultivation requires calculating Leaf VPD (LVPD). Two rooms with identical air sensors can have vastly different plant responses if the airflow or light intensity changes the leaf temperature.

The Ideal Ranges (The Goldilocks Zones)

While specific cultivars vary, most crops perform best within these general pressure ranges (measured in kPa):

-

Clones/Seedlings (0.8 kPa): Low suction. High humidity reduces stress while roots are forming.

-

Veg (1.0 kPa): Medium suction. Balanced transpiration supports rapid nutrient uptake and fast structural growth.

-

Flower (1.2–1.5 kPa): High suction. Slightly drier air encourages water uptake (driving P-K boost) and reduces mold risk for dense colas.

The SUNSCAPE Performance Standard: VPD as a Control System

Now that you understand how Vapor Pressure Deficit governs transpiration, nutrient uptake, and CO₂ exchange, the next step is applying it with precision.

VPD cannot be optimized in isolation. It must be synchronized with your lighting (PPFD), your irrigation shots, and your substrate dry-backs.

Book a discovery call with SUNSCAPE to unlock the SUNSCAPE Performance Standard.

Backed by 8 years of real cultivation data, we have established stage-specific VPD, temperature, and humidity baselines aligned to 63- to 73-day flowering cycles across more than 500 genetics.

Let us help you eliminate the guesswork. We will show you how to align your PPFD, DLI levels and spectrum tuning with a VPD-driven environment—turning your grow room into a repeatable, performance-controlled system.

Reference

Pulse Grow. (n.d.). The Ultimate Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD) Guide. Pulse Labs Resources.